The modern death

The fiction is radically real: at the end of the 1970s, the Swedish government (project group: DELLEM) invites people to a secret symposium on the subject of “The last stage of man’s life”. The real issue is how to get rid of the overaged society that we can no longer afford or want to afford. The question of how to kill the unproductive elderly and other superfluous people in the most humane way possible is discussed in a very practical way. Terrorist methods are of course far removed from an enlightened welfare state like Sweden, where the common good takes precedence over self-interest.

Wijkmark was obviously several decades ahead of the times, and what he had to say is still unpleasant today.

In Carl-Henning Wijkmark’s experimental literary work “The Modern Death”, a medical ethicist, a writer and intellectual historian and – almost ironically short – a theologian have their say alongside the inviting ministerial director Bert Persson. With the exception of the writer, all the experts agree that the main thing that is needed is to convince the population of the harmful effects of selfishly clinging to one’s own life, and how much it threatens the country’s economic future. First published in 1978, the book was only translated into German in 2001, both times without any great response. Wijkmark was obviously several decades ahead of the times, and what he had to say is still unpleasant today. One has to bear in mind that an age of 80 is considered crassly high in the book. We are only smiling about that today.

In today’s times, in which the elderly with their many voices stand in the way of important reform projects (think of the vote on brexite or even blockades on climate protection), and in addition impose immense costs on us young people through their pension entitlements and health and care costs, they are now exposed to an immense threat from the corona virus Sars-CoV-2, which we must combat with an economic counter-catastrophe that not only robs us young people of the air we breathe. (Note: as is becoming increasingly clear, it is not only the old who are at risk, but also the young. Nevertheless, the elderly are proportionally the main risk group, so the considerations remain relevant.)

Drowned in the storm of corona headlines is the news that this year in Germany the elderly will receive an above-plan pension increase. A pensioner close to me already took this as an opportunity to announce the distribution of her pension increase to the young with a premature sense of shame. (Of course, the old are entitled to the pension increase.)

A good time to read the book again, also to remind myself of the moral arguments that Wijkmark’s medical ethicist Caspar Storm puts forward to explain the chains of decision making in the difficult situation of “triage”. Triage inevitably takes place when there are more sick or injured people than there are treatment options and it has to be decided who is treated and who is not.

Human value and social value

In Storm’s first example, only chances of survival are calculated: a severe brain haemorrhage with 10% chance of survival and a traffic accident with 50% chance of survival. “The case is clear, the hemorrhage must go.”

In the second example there is a choice between two people with the same chances of survival. One is mentally deficiant, the other a Nobel Prize winner. Again, the choice is clear to him: “In any case, I have never met a doctor who was so idealistic that he would have hesitated to save the Nobel Prize winner.” Here, human value and social value are determined and weighed against each other. In times of euthanasia, however, the answer was much easier.

In his third example, things become more complicated: First, there is the choice between a 20-year-old pianist (“a radiant promise for the music world”) and a 45-year-old lumberjack. While the young woman is single, the worker has a family with four underage children. Here the evaluation of social value is dominant and is the decisive factor for the lumberjack.

But while the doctors get to work, a 60-year-old government politician joins them, a bachelor who has drunk and hit a tree. To my surprise, the medical ethicist chooses the politician and justifies this with the Catholic moral view that the social value of a politician can be regarded as so great that he is given the highest priority: “He must be saved for the sake of the state, which according to modern criteria is the highest of all values, even if we prefer to call it ‘society'”. Incidentally, the politician also beats the Nobel Prize winner. Nor does the medical ethicist hide the fact that the Nobel Prize winner would not benefit from his prize if he were a Nobel Prize winner in literature. As a man of letters, he would be at the very bottom of the class, together with the pianist, and would have only a cultural, aesthetic and hobbyistic social value, with only marginal economic value, i.e. dispensable.

We would be the first to be sorted out.

The virologist Christian Droste recently described our profession as “fun events”, certainly not maliciously. But one more reason for us artists to stay at home and healthy, and thus help to ensure that the triage situation does not occur. We would be the first to be sorted out. Although, with my family, I might have a chance to survive.

The game is over

Wijkmark’s writer Axel Rönning reacts to this with great pathos in his replica, and I can, of course, totally identify myself with this as an opera composer. In fact, in my opera “Happy Happy” (2014), I adopted this pathos as a defining emotion: I invented my protagonist as a singer who actually only wants to sing, but who constantly has to justify herself to society for not bringing any added value.

“We’ve got you now, you dog! We couldn’t kill your life properly, but when you die we want to do a good job. Individual? Integrity? Don’t talk nonsense. We’re just doing our job. We’ve been after you for a long time. We forbade you to play in the yard, wrote you down when you smoked in secret, bullied you all your life with forms and computers. Everything that was yours in your life we wanted to kill, you should produce crap that society needs and not your own inventions. You escaped for a long time and thought you were free and alive, but we were expecting you and today we take revenge. Now you are being sucked in, now you are here, now you are taking revenge for putting conscience before adaptation, fantasy before everyday life, freedom before security, the world before isolation – in short, not being dead enough. We are the Knickers, we are the Puritans, now comes the injection, now a hole is being punched, we are the death computer parvenus – the last hole, and the game is over. Now you are one of us, just as dead as we are. You shall become manure and fertilizer, and finally of little use. And away with him and in with the next! Here employment is promoted, here space is made for security, the youth before!”

Unfortunately, it is complex and laborious to defend humanism argumentatively.

This lets Wijkmark speak the writer Rönning as a parenthesis, as a personal expression of the writer for what he feels in the face of the social developments presented in the symposium. I would also like to believe that this monologue Alter Ego represents the author’s own emotion. As an intellectual historian, Rönning now presents a treatise on the historical development of human rights and human dignity as natural law. His intellectual demands sometimes overtax not only me as a reader, but obviously also the utilitarian thinkers of the fictitious group of experts. I recognize that in today’s discussions as well. Unfortunately, it is complex and laborious to defend humanism argumentatively, and it is laborious to recognize it as irrefutable in a world facing such massive practical problems. Why irrevocable? Because otherwise we open doors and gates back to barbarism.

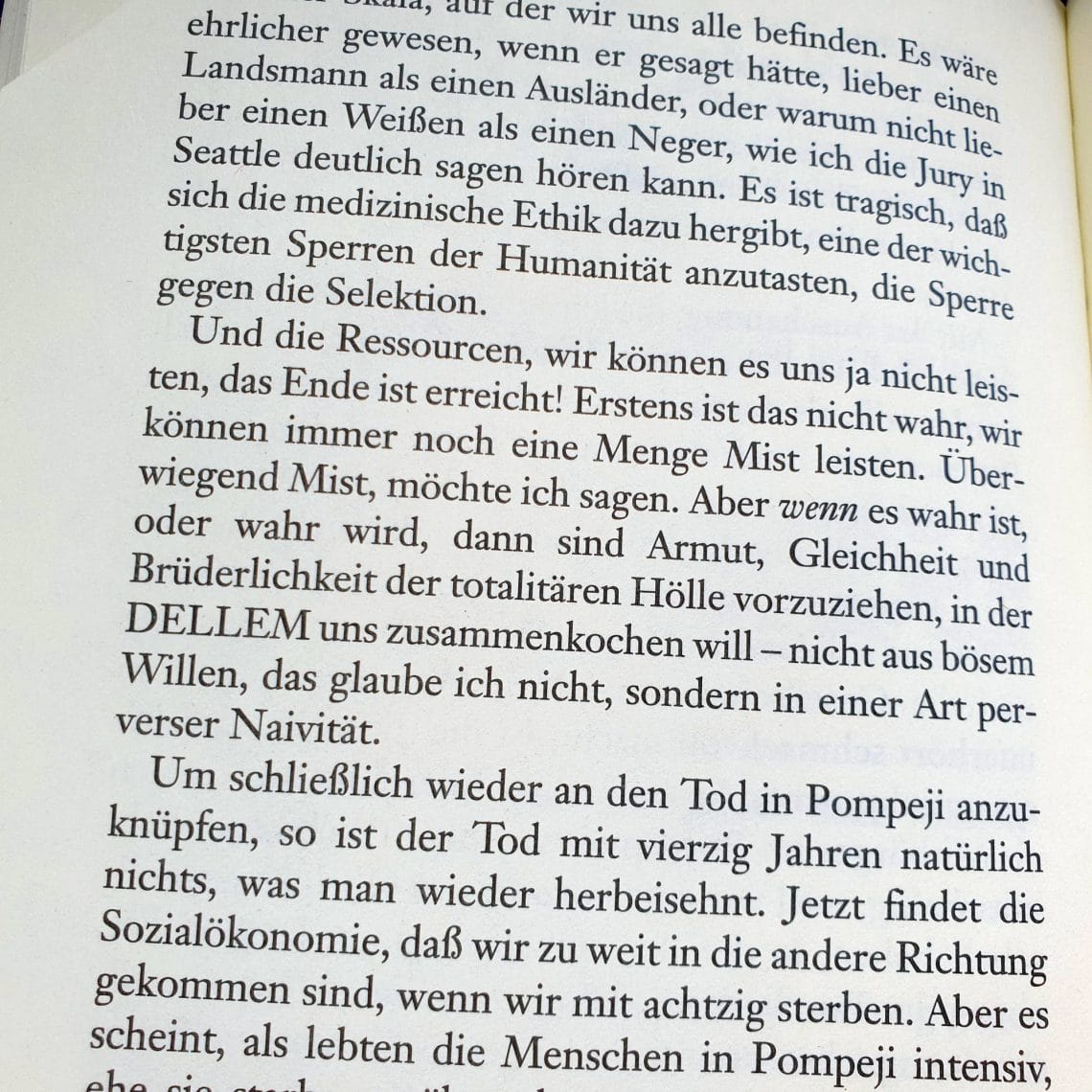

Rönning: “Better to save a Nobel Prize winner than a mentally deficient person, says Mr. Storm. But the imbecile and the Nobel Prize winner are only opposite poles on a scale on which we all find ourselves. It would have been more honest if he had said he would have preferred a fellow countryman to a foreigner, or why not a white man to a negro, as I can clearly hear the jury in Seattle. It’s tragic that medical ethics should be allowed to touch one of the most important barriers to humanity, the barrier against selection.”

A gigantic price tag

Back to today: ” Bringing the economy back to money is a much more reversible thing than bringing people back to life,” Bill Gates recently said in a TED conversation on how humanity should respond to the coronavirus. He expects the gigantic price of $4 trillion that this crisis will cost the world economy. But by and large “on a global scale, this matter will be over in two to three years”. Even the left-wing intellectual Noam Chomsky, who is certainly not suspected of any system conformity, advises serenity and reminds us that we will survive the coronavirus, but the consequences of global warming are irreversible.

Let us not give up the ideals of humanism above our completely justified and cruel fear of existence.

Let us not give up the ideals of humanism above our completely justified and cruel fear of existence. Let us help to prevent the spread of the virus. A situation of triage on a global scale is, in all its consequences, much worse than the serious cuts in our lives that we will have to struggle with for a long time to come.

(Translated with the help of deepl.com/translator)

Der moderne Tod

Vom Ende der Humanität

Carl-Henning Wijkmark

Gemini Verlag Berlin, 2001

Aus dem Schwedischen von Hildegard Bergfeld

Die Originalausgabe „Den moderna döden“ erschien 1978 im Verlag Cavefors.

https://www.matthes-seitz-berlin.de/buch/der-moderne-tod.html